Hello All,

The Northwest Passage, an impressive Arctic sea route connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, has long captivated the imagination of sailors and explorers. Now, One Ocean has departed Nome, Alaska and is heading toward this daunting and thrilling route, one that many around the world dream of attempting.

But this passage is changing in ways that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago. Once blocked by thick, multi-year sea ice that crushed wooden ships and halted exploration, parts of the Northwest Passage now open each summer. This shift is attracting adventurous sailors and commercial vessels alike. Yet beneath this new accessibility lies a much deeper story, one of profound environmental transformation.

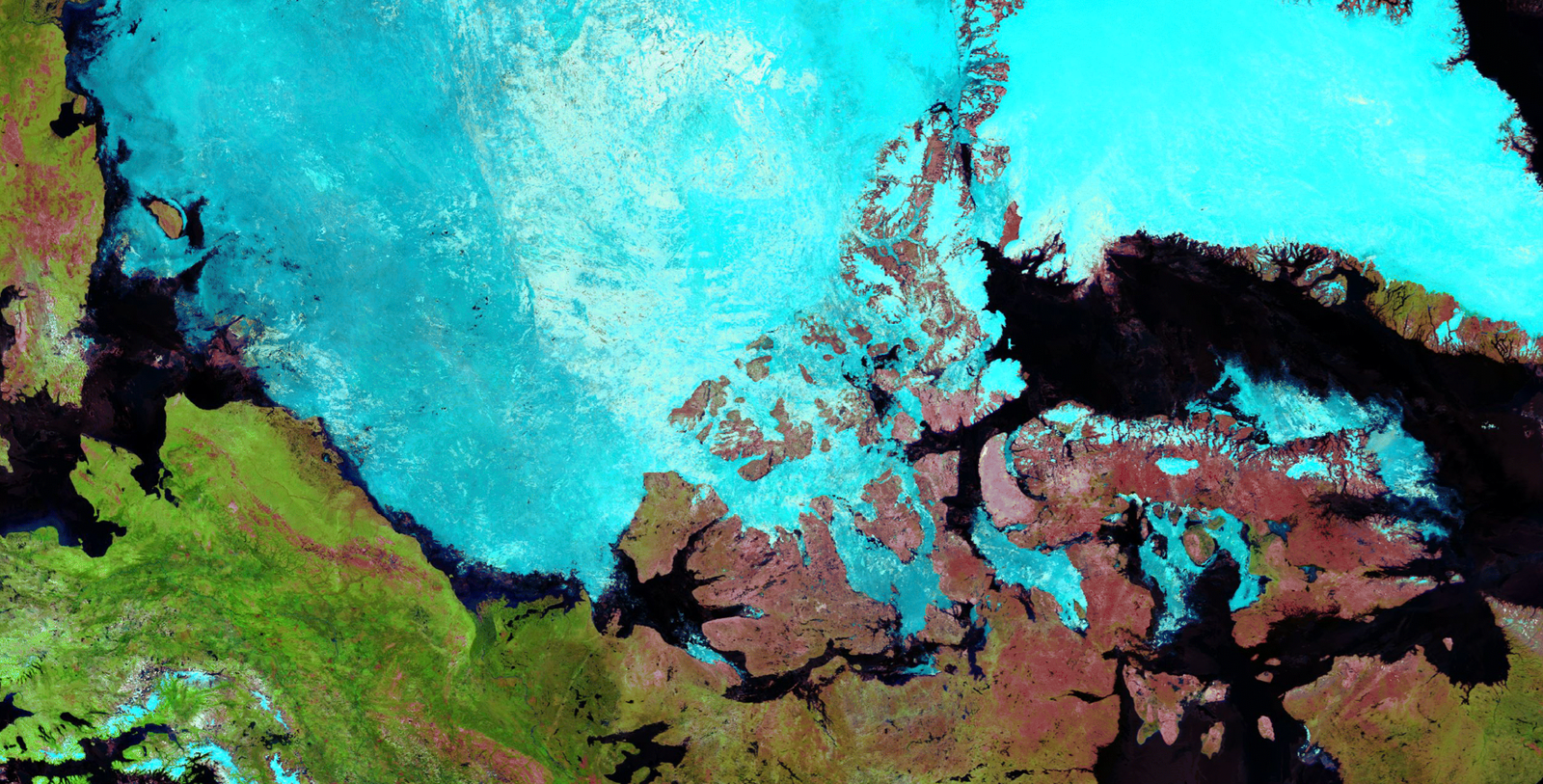

As we sail through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, we are not only navigating a remote and treacherous landscape. We are witnessing a region being rapidly reshaped by climate change.

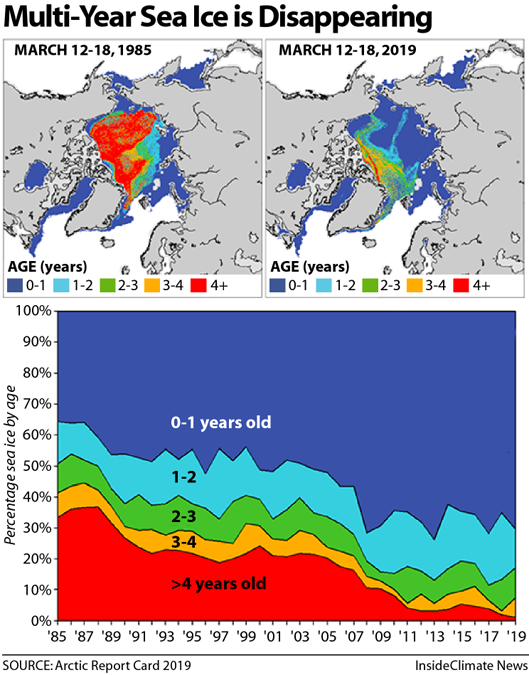

Arctic sea ice forms when ocean water freezes during the long, dark winters, blanketing vast areas of the Arctic Ocean. In the summer, a portion of this ice melts and recedes. This seasonal cycle is natural. What is no longer natural is the degree to which the extent, thickness, and duration of this ice have changed. Historically, the Northwest Passage was dominated by multi-year ice, which survives multiple melt seasons and becomes thicker, denser, and harder to break through. Today, that ice is vanishing. In its place, first-year ice, which is thinner, less stable, and more prone to break-up, has become increasingly common.

The Arctic is warming nearly four times faster than the rest of the planet. This phenomenon, known as Arctic amplification, is driven by a feedback loop. As ice melts, it exposes the darker ocean beneath, which absorbs more solar energy than reflective ice. That absorbed heat warms the water and causes more ice to melt, and the cycle continues. This process is contributing to the rapid decline of sea ice across the Arctic. Since satellite monitoring began in 1979, Arctic sea ice at its annual minimum in September has decreased by roughly 12% per decade. The ice-free window in the Northwest Passage is now several weeks longer than it was just 30 years ago. In recent years, satellite observations revealed record-low coverage of multi-year ice in parts of the Canadian Arctic. Some channels that were once sealed tight throughout the summer are now navigable for longer periods than ever before.

The consequences of this ice loss go far beyond navigation. The Arctic is home to highly specialized ecosystems that depend on stable ice conditions to function. Polar bears, for example, rely on sea ice to hunt for seals. As the ice forms later in the year and melts earlier, these predators must swim farther and expend more energy to find food. Many are losing body mass, reproducing less often, and appearing more frequently in northern communities in search of food.

Marine mammals such as belugas, narwhals, and bowhead whales follow established migratory corridors and depend on predictable ice patterns. The rapid changes in sea ice conditions and water temperatures are disrupting these migrations and increasing the risk of ship collisions and noise disturbances. At the base of the food web, microscopic algae that grow on and under sea ice serve as a critical food source for zooplankton, fish, seabirds, and marine mammals. When sea ice vanishes, the entire web becomes destabilized.

Migratory birds that breed in the Arctic, such as snow geese and eiders, are experiencing shifts in their breeding seasons along with increased predation and the loss of habitat due to thawing permafrost. These ecological shifts are compounded by the human impacts of a warming Arctic, which are felt most acutely by Indigenous and northern communities.

For people who have lived with and understood Arctic ice for generations, its disappearance is not a distant or abstract phenomenon. It is a daily, lived experience. Elders who once read the ice with accuracy and passed down vital knowledge are finding that traditional routes used for hunting, travel, and trade are no longer safe. Trails that were once stable throughout the winter now melt early or become dangerously thin.

Subsistence hunters and fishers are finding it more difficult to track and harvest animals like seals, walrus, and caribou, as migration patterns shift and ice-dependent species become less accessible. This is not just an ecological concern; it is a threat to food security and cultural continuity. As the permafrost thaws, essential infrastructure such as homes, airstrips, and roads is collapsing or buckling. At the same time, coastal erosion and flooding are becoming more frequent as open water and storms gain ground where sea ice once provided protection.

Increased access to the Arctic is also drawing in a surge of interest from commercial shipping, cruise tourism, and resource extraction. As cargo ships, tankers, and other vessels move into previously inaccessible waters, they bring with them new risks including oil spills, marine noise pollution, invasive species, and disruption to wildlife and sensitive habitats. Communities are raising concerns about the lack of oversight, environmental protections, and long-term planning, especially as global powers compete for control and influence in a rapidly opening Arctic.

Despite this growing accessibility, the Northwest Passage remains one of the most dangerous maritime routes on Earth. Ice conditions are still highly unpredictable. Winds and currents can suddenly shift ice floes into narrow channels, trapping vessels that passed through easily just hours before. Multi-year ice, though less common, still exists and poses a serious threat to sailboats and smaller ships not reinforced for ice. Arctic storms, intensified by reduced ice cover, can build quickly, generating steep seas and poor visibility. Charts for many parts of the Arctic remain incomplete or outdated, and uncharted rocks or shifting shoals can pose deadly risks. Freezing spray, fog, and limited daylight further complicate navigation. There are few ports of refuge, minimal search and rescue infrastructure, and very limited satellite coverage in remote areas. If a vessel runs into trouble, help may be days away. For all its beauty, the passage remains a remote, high-stakes environment that demands caution, preparation, and respect.

While the melting ice might make the Northwest Passage more tempting for sailors, it should also be seen as a clear warning. This is not just a matter of changing navigation routes. It is a sign of a world in flux. The Arctic is one of the most important indicators of climate change, and it is offering a glimpse into the global future. We are already witnessing faster-than-expected warming, collapsing ecosystems, the erosion of traditional ways of life, and rising sea levels that will impact people far beyond the polar regions.

And once the Arctic ice is gone, we will not get it back, at least not in any human timeframe. While some changes are already locked in, there is still time to act. Global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions must accelerate if we hope to preserve what remains of this critical region. Indigenous leadership must be at the center of Arctic conservation and governance efforts, drawing on traditional knowledge and lived experience. Stronger regulations are needed to guide Arctic shipping activity, including speed limits, emissions controls, and mandatory ice navigation training for all vessels operating in the region. Investment in research and monitoring must continue because what happens in the Arctic affects every corner of the Earth.

As we sail through the Northwest Passage, we are not just tracing a line across a map. We are moving through a region undergoing profound transformation. The open water we see is not merely a sign of progress. It is a sign of loss, of resilience, and of urgent change. To witness the melting of Arctic ice is to watch history unfold in real time. Ancient, interconnected systems are breaking down before our eyes.

For those of us fortunate enough to see it, document it, and share it, there is a responsibility. A responsibility to learn, to listen, to teach, and to help protect what remains.

From the Field,

Grace